English version is below

Дедалі більше українських ресторанів з’являється зараз за кордоном. З одного боку, на це вплинула велика хвиля еміграції українців за кордон, а з іншого – цікавість іноземців: хто ж такі українці і що вони їдять?

Борщ, вареники, голубці, сирники – ці назви вже входять у ресторанні меню за кордоном.

Наталя Бас, співвласниця ресторану The Boršč У Празі, застала ще ті часи, коли наш український борщ позиціонувався у ресторанах як «рускій борщ». Зараз часи змінились і наша кухонна культурна дипломатія перемагає.

Тож вона поділилась зі Справжніми історіями своїми роздумами про просування української кухні у світі.

Українці – це не єдина наша цільова аудиторія

Коли українці приходять до ресторану, то вони все переважно оцінюють з позицій: а як моя мама чи бабуся готували. І, звісно ж, їм здається, що їхні рідні готували краще, і буряк терли краще, і загалом все краще робили. Ця аудиторія сувора така, що ой-йой.

Також ще один дуже популярний коментар, який ми чуємо від українців: та я це вдома зварю, та в мене це в холодильнику стоїть.

Цікаво, що за якийсь бургер, інше людина платить біля 300 крон, і її це влаштовує, а в нас 200 крон за котлету по-київськи – дуже дорого. Хоч наші страви, як ми знаємо, складні в приготуванні. Тому що для наших людей – це занадто домашнє, занадто знайоме, занадто з дитинства – от за це платити дорого. Це як для мене було занадто дорого платити за ожину в супермаркеті. Тут вона дуже дорога, малесенька коробочка, звідкись там приїхала з Іспанії, коштує страшенних грошей, а в моєму кримському дитинстві її було багато, і вона весь двір обплітала.

З чого почалася наша справа

Ми сім’я айтівця, переїхали через роботу мого чоловіка в 2017 році до Праги. Мали гроші, щоб почати купувати квартиру, зробити перший внесок в іпотеку, але зрозуміли, що хочемо чогось більшого. І з’явилась така місія – зробити місце з українськими стравами.

Ми в якийсь момент усвідомили, що нам набридло бачити «рускій борщ», який так скрізь називався. І ми такі: що за прикол? Ні.

Звідки переїхали? Років 10 жили в Києві, але народилися в Кропивницькому.

Тож вклали гроші, які у нас були «подушкою», у цю справу. Почали відкриватись, це було довго, було нелегко, робили великий ремонт, вентиляційну систему. Були зелені, неосвічені, і не зрозуміли, що взяли дуже погане приміщення. Вкладалися так, що руки опускалися. Але через те, що в нас була місія знайомити чехів і іноземців з українською кухнею, не шароварно, не гоп-гоп, а просто створити нормальний заклад, то ми йшли вперед.

Ми стараємось, щоб було менше фольклорності, більше сучасності і нагодувати відвідувачів хорошими українськими стравами. Тоді ми були першими, зараз уже більше 10 українських ресторанів у Празі. Нас багато, я радію.

Чи вони конкуренти? Ні. Що ми ділимо? Ми ще занадто екзотика. От коли ми будемо, як в’єтнамці тут, на кожному кроці будуть борщі й вареники, от тоді можна буде казати про конкуренцію.

Чим ми беремо

Ми сноби, і вирішили, що не будемо гратися, як 99 відсотків наших колег, у збірну солянку. Ми не називаємо українською кухнею салат олів’є, шашлики, пельмені, ми не будемо робити це. Ми не будемо робити те, що в нас усі готували під час радянського союзу. Я не хочу. Воно нас не представляє і не має представляти. А ще українці афігенно ліплять суші, може, навіть краще, ніж азіати. Але ми не кажемо, що суші будуть представляти Україну в українському закладі. Ми розкішно варимо пасту, скільки українців італійських закладів відкрило, скільки жінок із заробітків повернулось, і вміють так готувати італійські страви, що італійців дивують. Але це не значить, що воно нас представляє. Так само я наполягаю, що жодні пельмені ніколи не будуть представляти українську кухню.

Тож ми відкрили заклад, в якому тільки українська кухня.

Я спробувала зібрати якнайбільше книг зі старовинними рецептами

У мене є книжка «Страви й напитки», якось так вона називається, з 1912 року, там унікальна мова і дуже багато цікавих назв страв і продуктів, я їх не знаю, і способу їхнього приготування, і навіть посуду, у нашому побуті зараз немає такого. Книжка несе велику цінність, бо багато у нас рецептів втрачено, заборонено, перероблено. Всі шукають якийсь горошок, щоб його в олів’є кинути.

Українська кухня не обов’язково сільська й дуже проста

Ще до «совкових» часів, ясно, що була кухня з різними рябчиками, куріпками, паштетами, була вишукана кухня.

Було і різноманіття, не пошук просто поїсти після важкої роботи в полі, а також отримати задоволення від їжі. Українці багато сквашували, у нас ще й кухня з високою харчовою цінністю. Багато квашенини, ферментації, в цьому ми схожі з азіатами – корейцями, японцями.

У нас було стільки цікавих старовинних рецептів!

Наприклад, ми продаємо напій, який називається контабас Він також є у цій книзі 1912 року, що мене неймовірно потішило. Це український алкогольний напій, 40 градусів, виготовляється з бруньок чорної смородини, тільки 4 дні в році це насправді можна зробити – зібрати ці бруньки. А зараз цей спосіб відроджений, і це дуже дорогий напій. І неймовірно ароматний, дуже смачно пахне чорна смородина, дуже міцний, прикольний.

Найбільше іноземців в нашій кухні дивують наші смаки

Я пам’ятаю, ще давно дуже любила влаштовувати вдома борщ-вечірки, запрошувала іноземців, варила велику каструлю борщу, і хтось міг сказати – о, а чому ви зварили салат? Хтось не розумів взагалі першу страву як концепцію.

Я ще часто кажу, що нам пощастило, бо в Чехії є культура споживання перших страв. Тут є свої супи, перші страви, вони самі багато їдять перших страв. Загалом у Чехії є ця культура сісти і нормально поїсти перше, друге, третє. І в нашій культурі це є. А в інших – немає. Тож в іншому місці наш концепт був би не зрозумілий, до нас би ходила маленька українська діаспора, і все.

Чи легко вести бізнес в Чехії

Я ніколи не вела бізнес в Україні, але дуже багато спілкувалась з українськими ресторатами, і, судячи з того, що почула від них – у Чехії легше.

Бюрократія тут є, вона досить така стара, але тут абсолютно немає такого, щоб занести комусь хабарі. Клянусь, немає такого, у мене 2 заклади. А в Україні на цьому багато чого будується, ти коли бізнес-план робиш, розумієш, що тобі треба буде занести пожежникам, іншим, щоб отримати дозволи. Тут немає такого поняття – дозвіл на відкриття закладу. Коли ти починаєш бізнес ресторанний, ти проходиш ревізії, чи не стара в тебе проводка тощо, але ти не просиш дозволу відкритись, ти відкриваєшся, повідомляєш, що ти відкриваєшся чи закриваєшся, і все.

Ми є в базах, до нас можуть прийти, але ми не просили дозволу відкриватись. І вже наша відповідальність – чи ми відкрилися законно. У Чехії легше, тут є презумпція невинуватості. А в Україні – ти винен спочатку, що в тебе те й те неправильно. А тут – зроби правильно, і тоді тебе не оштрафують.

Які цікаві історії можу пригадати?

Багато цікавих. От із недавніх – прийшла пара французів, і в них був із собою путівник французькою мовою по Празі: подивитися такі-то місця, історії храмів, також місця, де варто поїсти. І там був наш ресторан. І було написано, що це взірець національної кухні, перераховано страви, висока оцінка. Було приємно.

Ми чесні в тому, що ми робимо, не стрибаємо між кухнями, концепціями, і це зазвичай приводить до успіху. Будь собі вірний, гни свою лінію, тобі кажуть – давай додамо окрошечку, а ти: ні, цього не буде.

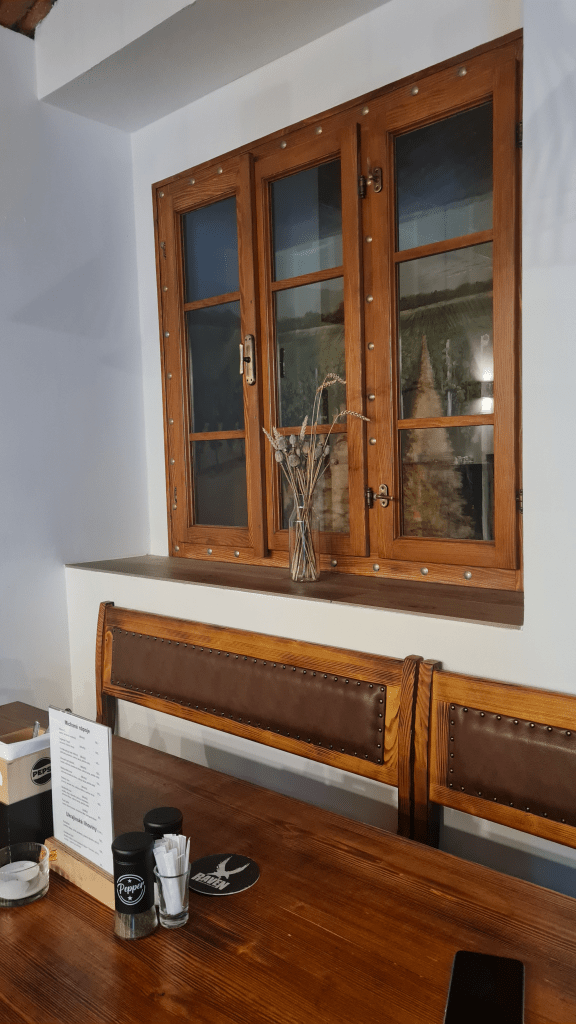

Фото:

Справжні історії;

Anton Filonenko

—-

Article in English:

There is more and more borscht in the world

More and more Ukrainian restaurants are opening abroad today. On the one hand, this is driven by the large wave of Ukrainian emigration; on the other, by foreigners’ curiosity — who Ukrainians are and what they eat.

Borscht, varenyky, holubtsi, syrnyky — these names are now appearing on restaurant menus around the world.

Natalia Bas, co-owner of The Boršč restaurant in Prague, remembers the times when our Ukrainian borscht was marketed in restaurants as “Russian borscht.” Today, things have changed, and our culinary cultural diplomacy is winning.

She shared her reflections with Real Stories about promoting Ukrainian cuisine globally.

Ukrainians are not our only target audience

When Ukrainians come to the restaurant, they usually judge everything from the perspective of “how my mom or grandma used to cook it.” And, of course, they feel that their family always cooked better — the beets were grated better, everything was done better. This audience is, oh boy, extremely demanding.

Another very common comment we hear from Ukrainians is: “I can cook this at home,” or “I’ve already got this in my fridge.”

What’s interesting is that people will easily pay around 300 CZK for a burger somewhere else and be perfectly fine with it, but 200 CZK for Chicken Kyiv at our place suddenly feels “too expensive.” Even though, as we all know, our traditional dishes are far more complex to prepare. But for our people, it’s simply too homemade, too familiar, too tied to childhood — something they don’t feel is worth paying much for.

It’s like my own experience with blackberries at the supermarket. Here they’re incredibly expensive — a tiny little box shipped from Spain costs a fortune. But in my Crimean childhood, blackberries grew everywhere; they covered the whole yard. Paying a lot for them now still feels strange.

How Our Venture Began

We’re an IT family who moved to Prague in 2017 because of my husband’s job. We had enough savings to start buying an apartment and make a down payment on a mortgage — but we realized we wanted something bigger. That’s when the idea, almost a mission, appeared: to create a place that serves Ukrainian food.

At some point we became genuinely tired of seeing “Russian borscht” everywhere on menus. It was always called that. And we thought: What is this nonsense? No. Absolutely not.

Where did we come from? We spent about ten years living in Kyiv, but we were born in Kropyvnytskyi.

So we invested the savings we had — our “safety cushion” — into this venture. The opening process was long and difficult: major renovations, a new ventilation system. We were inexperienced, naïve even, and didn’t realize we had chosen a very unsuitable space. We kept pouring money into it to the point that our hands were almost giving up. But because we had a mission — to introduce Czechs and foreigners to Ukrainian cuisine, without clichés, without “folk costume” aesthetics, but through a genuinely good, contemporary restaurant — we kept moving forward.

We try to keep folklore to a minimum and focus instead on modernity and on serving truly good Ukrainian dishes. Back then, we were the first. Now, there are more than ten Ukrainian restaurants in Prague. There are many of us now, and I’m genuinely happy about it.

Are they competitors? No. What is there to compete for? We’re still too exotic. When we become like the Vietnamese community here — when borscht and varenyky are on every corner — then we can start talking about competition.

What Sets Us Apart

We’re a bit of snobs, and we made a conscious decision not to play the same game as 99% of our colleagues — the “mixed-everything-together” approach. We don’t call Olivier salad, shashlik, or pelmeni “Ukrainian cuisine,” and we’re not going to. We won’t cook what everyone made during the Soviet times. I don’t want that. It doesn’t represent us — and it shouldn’t.

And yes, Ukrainians make amazing sushi, maybe even better than some Asians. But that doesn’t mean sushi should represent Ukraine in a Ukrainian restaurant. We cook pasta brilliantly too — so many Italians are surprised by how well Ukrainians prepare Italian dishes, especially women who returned from working in Italy. But that still doesn’t mean pasta represents Ukrainian cuisine.

And just as strongly, I insist that pelmeni will never represent Ukrainian food.

So we opened a place that serves only Ukrainian cuisine.

I tried to collect as many old cookbooks with traditional recipes as possible

I have a book called “Dishes and Drinks” — something like that — from 1912. The language in it is extraordinary, and it includes so many fascinating dish names, ingredients, and cooking methods that I’ve never heard of. Even the cookware mentioned there doesn’t exist in our everyday life anymore.

The book is incredibly valuable because so many of our recipes were lost, forbidden, or altered over time. Meanwhile, everyone today is just looking for canned peas to throw into an Olivier salad.

Ukrainian cuisine is not necessarily rustic or overly simple

Before the Soviet era, it was clear that our cuisine included refined dishes — hazel grouse, partridges, pâtés — there was a whole elegant culinary tradition. There was variety, not just the need to “refuel” after a long day in the fields, but also the desire to enjoy food.

Ukrainians fermented a lot; our cuisine is rich in nutritional value. Fermentation, pickling — in this, we are similar to some Asian cultures, like Koreans and Japanese.

We had so many fascinating traditional recipes!

For example, we sell a drink called kontabas. It also appears in that 1912 book, which delighted me immensely. It’s a Ukrainian alcoholic drink, about 40% alcohol, made from black currant buds — and you can only make it during a four-day window each year, when those buds can actually be collected. This method has now been revived, and the drink is very expensive. And incredibly aromatic — the black currant scent is wonderful. It’s very strong, unusual, and really cool.

What surprises foreigners most in our cuisine are our flavors

I remember how, long before the restaurant, I loved hosting borscht parties at home. I’d invite foreigners, cook a huge pot of borscht — and someone might say, “Oh, why did you make a salad?” Some people simply couldn’t understand the concept of a first course at all.

I often say we’re lucky to be in the Czech Republic, because there is a strong culture of eating soups. They have their own soups, they eat first courses regularly. In general, Czechs have this tradition of sitting down for a proper meal: a first course, a main course, and even a dessert. And we have this in our culture too. Many other cultures don’t.

So in another country, our concept might not have worked — only a small Ukrainian diaspora would come, and that would be it.

Is it easy to run a business in the Czech Republic?

I’ve never run a business in Ukraine, but I’ve spoken a lot with Ukrainian restaurateurs, and judging from what I’ve heard, it’s easier in the Czech Republic.

There is bureaucracy here, and it’s rather old-fashioned, but there is absolutely no such thing as giving bribes. I swear — it simply doesn’t exist, and I have two restaurants. In Ukraine, a lot is built around this: when you create a business plan, you already understand that you’ll have to “pay” the fire inspectors or someone else to get permits.

Here, there is no such concept as a “permit to open a restaurant.” When you start a restaurant business, you go through inspections — they check your wiring, your equipment, things like that — but you don’t ask for permission to open. You just open, inform them that you’re opening or closing, and that’s it.

We’re in the registry, they can come to check us, but we never asked anyone for the right to open. And then it’s our own responsibility to make sure we opened legally. In the Czech Republic, it’s easier — there is a presumption of innocence. In Ukraine, you’re “guilty” from the start, as if you’ve already done something wrong. Here it’s simple: do everything correctly, and you won’t get fined.

What interesting stories can I remember?

There are many. One of the recent ones: a French couple came in carrying a French-language travel guide to Prague — the kind that lists places to visit, the history of churches, and also where to eat. And our restaurant was in that guide. It said we were an example of national cuisine, listed our dishes, gave us a high rating. That was really touching.

We’re honest about what we do — we don’t jump between cuisines or concepts — and that usually leads to success. Stay true to yourself, stick to your vision. People might say, “Come on, add some okroshka to the menu,” and you just say: “No, that’s not going to happen.”

Photo:

Spravzhni Istoriyi;

Anton Filonenko

Хочете підтримати нас?

Кожен ваш донат допоможе ще активніше розвивати наш некомерційний проєкт, який активно працює вже більше 3 років.

Справжні історії – просвітницький проєкт, який на волонтерських засадах розповідає цікаві історії про Україну, відомих українців, подорожі, традиції, звичаї, кухню, а також захопливі історії про мандрівки світом та відомих особистостей у світі.

У наших планах – створення також англомовної версії сайту, щоб світ більше дізнався про Україну та українців.

Наші рахунки:

Картка у грн.: 5363 5421 0596 6718

Підтримати проєкт

Want to support us?

Each of your donations will help our non-commercial project, which has been producing stories for you for already three years, to become even better.

True Stories is an educational project that, on a volunteer basis, tells interesting stories about Ukraine, famous Ukrainians and other inspiring people, travels, traditions, customs, and cuisine.

Our plans include the creation of an English-language version of the site so that the world can learn more about Ukraine and Ukrainians.

Support the project

Підтримати проєкт

1,00 $